Principles for System Optimization

Published:

Strategies to improve the performance or efficiency of the system

Trivia

According to Prof. George Varghese, the author of the book, Network Algorithmics has four idols in life:

- The first is Leonard Bernstein, who taught him in his lectures on music that a teacher’s enthusiasm for the material can be infectious.

- The second is George Polya, who taught him in his books on problem solving that the process of discovery is as important as the final discoveries themselves.

- The third is Socrates, who taught him through Plato that it is worth always questioning assumptions.

- The fourth is Jesus, who has taught him that life, and indeed his book on Network Algorithmics, is not a matter of merit but of grace and gift.

As a grateful student of his class, he was our Leonard Bernstein, who made us infected and dangerous with his enthusiasm for the music of Algorithmics.

Prologue

The principles are the strategies, which should be employed while trying to improve the performance or efficiency of the system. These are those secret formulas, that have been widely used across network implementations in the days of internet, when it was notoriously unreliable to bring it to the current magical state today by tackling and overcoming implementation bottlenecks. These are those recipes, that helped OS evolve from early batch system, then multi-programming and time-sharing systems, followed by real time systems to the current generation of distributed and networked operating systems.

These optimization principles are vastly based on Network Algorithmics, a field of study which resolves networking bottlenecks using interdisciplinary techniques that include changes to hardware and operating systems as well as efficient algorithms; they are paraphrased from the book — “ Network Algorithmics” by Varghese, George. Lets delve into the seventeen principles with an interdisciplinary thinking across systems:

Principles

Systems Lego Principles

The first 5 principles take advantage of the fact that a system is constructed from subsystems. By taking a systemwide rather than a black-box approach, one can often improve performance.

1. Avoid obvious waste in common situations

In a system, there may be wasted resources in special sequences of operations. If these patterns occur commonly, it may be worth eliminating the waste. This reflects an attitude of thriftiness toward system costs.

Notice that each operation considered by itself may have no obvious waste. It is the sequence of operations that have obvious waste. Clearly, the larger the exposed context, the greater the scope for optimization. While the identification of certain operation patterns as being worth optimizing is often a matter of designer intuition, optimizations can be tested in practice using benchmarks.

2. Shift computation in time

Systems have an aspect in space and time. The space aspect is represented by the subsystems, possibly geographically distributed, into which the system is decomposed. The time aspect is represented by the fact that a system is instantiated at various time scales, from fabrication time, to compile time, to parameter-setting times, to run time. Many efficiencies can be gained by shifting computation in time. Following are five generic methods that fall under time-shifting:

2a. Precompute

This refers to computing quantities before they are actually used, to save time at the point of use. A common systems example is table-lookup methods, where the computation of an expensive function f in run time is replaced by the lookup of a table that contains the value of f for every element in the domain of f .

2b. Evaluate lazily

This refers to postponing expensive operations at critical times, hoping that either the operation will not be needed later or a less busy time will be found to perform the operation. First, putting off work might reduce the latency of the current operation, thus improving responsiveness. Second, and more importantly, laziness sometimes obviates the need to do the work at all.

2c. Share expenses, Batch

This refers to taking advantage of expensive operations done by other parts of the system. An important example of expense sharing is batching, where several expensive operations can be done together more cheaply than doing each separately.

2d. Overlap, Time sharing

Time sharing is a basic technique used by an OS to share a resource. By allowing the resource to be used for a little while by one entity, and then a little while by another, and so forth, the resource in question (e.g., the CPU, or a network link) can be shared by many.

When possible, overlap operations to maximize the utilization of systems. Overlap is useful in many different domains, including when performing disk I/O or sending messages to remote machines; in either case, starting the operation and then switching to other work is a good idea, and improves the overall utilization and efficiency of the system.

2e. Amortization

The general technique of amortization is commonly used in systems when there is a fixed cost to some operation. By incurring that cost less often (i.e., by performing the operation fewer times or for shorter time slice), the total cost to the system is reduced.

3. Relax system requirements

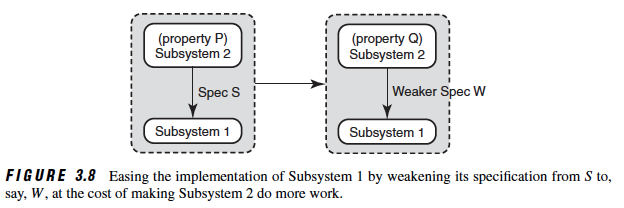

When a system is first designed top-down, functions are partitioned among subsystems. After fixing subsystem requirements and interfaces, individual subsystems are designed. When implementation difficulties arise, the basic system structure may have to be redone as follows:

Implementation difficulties can sometimes be solved by relaxing the specification requirements for, say, Subsystem 1. This is shown in the above figure by weakening the specification of Subsystem 1 from, say, S toW , but at the cost of making Subsystem 2 obey a stronger property, Q , compared to the previous property, P .

Three techniques that arise from this principle are distinguished by how they relax the original subsystem specification:

3a. Trade certainty for time

Systems designers can fool themselves into believing that their systems offer deterministic guarantees, when in fact we all depend on probabilities. This opens the door to consider randomized strategies when deterministic algorithms are too slow. In systems, randomization is used by millions of Ethernets worldwide to sort out packet-sending instants after collisions occur.

3b. Trade accuracy for time

Similarly, numerical analysis cures us of the illusion that computers are perfectly accurate. Thus it can pay to relax accuracy requirements for speed. In systems, many image compression techniques, such as MPEG, rely on lossy compression using interpolation.

3c. Shift computation in space

Notice that all the examples given for this principle relaxed requirements: Sampling may miss some packets, and the transferred image may not be identical to the original image. However, other parts of the system (e.g., Subsystem 2 in the Figure) have to adapt to these looser requirements. Thus we prefer to call the general idea of moving computation from one subsystem to another (“robbing Peter to pay Paul”) shifting computation in space.

3d. Space sharing

The counterpart of time sharing is space sharing, where a resource is divided (in space) among those who wish to use it like assigning same physical node to multiple clusters and sharing based on demand.

4. Leverage off system components

A black-box view of system design is to decompose the system into subsystems and then to design each subsystem in isolation. While this top-down approach has a pleasing modularity, in practice performance-critical components are often constructed partially bottom-up. For example, algorithms can be designed to fit the features offered by the hardware.

4a. Exploit locality

Exploit locality of reference. There are two basic types of reference locality — temporal and spatial locality. Temporal locality refers to the reuse of specific data, and/or resources, within a relatively small time duration. Spatial locality refers to the use of data elements within relatively close storage locations. Sequential locality, a special case of spatial locality, occurs when data elements are arranged and accessed linearly, such as, traversing the elements in a one-dimensional array.

Locality is merely one type of predictable behavior that occurs in computer systems. Systems that exhibit strong locality of reference are great candidates for performance optimization through the use of techniques such as the caching, prefetching for memory and advanced branch predictors at the pipelining stage of a processor core.

4b. Trade memory for speed

The obvious technique is to use more memory, such as lookup tables, to save processing time. A less obvious technique is to compress a data structure to make it more likely to fit into cache, because cache accesses are cheaper than memory accesses.

4c. Exploit existing hardware features

Understanding the underlying hardware and exploiting the hardware features across the layers of system abstraction can be difficult, but if done properly, can provide tremendous speed-up.

If this principle is carried too far, the modularity of the system will be in jeopardy. Two techniques alleviate this problem. First, if we exploit other system features only to improve performance, then changes to those system features can only affect performance and not correctness. Second, we use this technique only for system components that profiling has shown to be a bottleneck.

5. Add hardware to improve performance

When in doubt, use brute force.

When all else fails, goes the aphorism, use brute force. Adding new hardware, such as buying a faster processor, can be simpler and more cost effective than using clever techniques. Besides the brute-force approach of using faster infrastructure (e.g., faster processors, memory, buses, links), there are cleverer hardware-software trade-offs. Since hardware is less flexible and has higher design costs, it pays to add the minimum amount of hardware needed. In computer systems, dramatic improvements each year in processor speeds and memory densities suggest doing key algorithms in software and upgrading to faster processors for speed increases. But computer systems are abound with cleverer hardware-software trade-offs.

Decomposing functions between hardware and software is an art in itself. Hardware offers several benefits. First, there is no time required to fetch instructions: Instructions are effectively hardcoded. Second, common computational sequences (which would require several instructions in software) can be done in a single hardware clock cycle. Third, hardware allows you to explicitly take advantage of parallelism inherent in the problem. Finally, hardware manufactured in volume may be cheaper than a general-purpose processor.

On the other hand, a software design is easily transported to the next generation of faster chips. Hardware, despite the use of programmable chips, is still less flexible. Besides specific performance improvements, new technology can result in a complete paradigm shift. The following specific hardware techniques are often used:

5a. Use memory interleaving and pipelining

Interleaved memory is a design made to compensate for the relatively slow speed of dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) or core memory, by spreading memory addresses evenly across memory banks. That way, contiguous memory reads and writes are using each memory bank in turn, resulting in higher memory throughputs due to reduced waiting for memory banks to become ready for desired operations.

A pipeline, also known as a data pipeline, is a set of data processing elements connected in series, where the output of one element is the input of the next one. The elements of a pipeline are often executed in parallel or in time-sliced fashion, which improves the performance.

5b. Use wide word parallelism

Use wide memory words that can be processed in parallel. This can be implemented using DRAM and exploiting page mode or by using SRAM and making each memory word wider.

5c. Combine expensive and cheap resources effectively

For example, SRAM is expensive and fast and that DRAM is cheap and slow, it makes sense to combine the two technologies to attempt to obtain the best of both worlds. While the use of SRAM as a cache for DRAM databases is classical, there are many more creative applications of the idea of a memory hierarchy.

Principles for Modularity with Efficiency

Next five principles suggest methods for improving performance while allowing complex systems to be built modularly.

6. Create efficient specialized routines by replacing inefficient general purpose routines

Do one thing at a time, and do it well.

As in mathematics, the use of abstraction in computer system design can make systems compact, orthogonal, and modular. However, at times the one-size-fits-all aspect of a general purpose routine leads to inefficiencies. In important cases, it can pay to design an optimized and specialized routine. For example, many database applications replace the operating system caching routines with more specialized routines. It is best to do such specialization only for key routines, to avoid code bloat.

7. Avoid unnecessary generality

Don’t generalize; generalizations are generally wrong. Butler Lampson

The tendency to design abstract and general subsystems can also lead to unnecessary or rarely used features. Thus, rather than building several specialized routines as per principle 6 to replace the general-purpose routine, we might remove features to gain performance.

Exterminate features. C. Thaker

Of course, as in the case of principle 3 of relaxing system requirements , removing features requires users of the routine to live with restrictions.

8. Don’t be tied to reference implementation

Specifications are written for clarity, not to suggest efficient implementations. Because abstract specification languages are unpopular, many specifications use imperative languages such as C. Rather than precisely describe what function is to be computed, one gets code that prescribes how to compute the function. This has two side effects.

First, there is a strong tendency to over-specify. Second, many implementors copy the reference implementation in the specification, which is a problem when the reference implementation was chosen for conceptual clarity and not efficiency.

Implementors are free to change the reference implementation as long as the two implementations have the same external effects. In fact, there may be other structured implementations that are more efficient as well as modular.

9. Pass hints in module interfaces

A hint is information passed from a client to a service that, if correct, can avoid expensive computation by the service. The two key phrases are passing and correctness . By passing the hint in its request, a service can avoid the need for the associative lookup needed to access a cache. For example, a hint can be used to supply a direct index into the processing state at the receiver. Also, unlike caches, the hint is not guaranteed to be correct and hence must be checked against other certifiably correct information. Hints improve performance if the hint is correct most of the time. Incorrect hints must not jeopardize system correctness but result only in performance degradation.

This definition of a hint suggests a variant in which information is passed that is guaranteed to be correct and hence requires no checking. For want of an established term, we will call such information a tip . Tips are harder to use because of the need to ensure correctness of the tip.

As the system rarely knows what is best for each and every process of the system, it is often useful to provide interfaces to allow users or administrators to provide some hints to the system, which the system need not necessarily pay attention to it, but rather might take the advice into account in order to make a better decision.

10. Pass hints in message headers

For distributed systems, the logical extension to last principle is to pass information such as hints in message headers. For example, computer architects have applied this principle to circumvent inefficiencies in message-passing parallel systems such as the Connection Machine.

Principles for Speeding Up Routines

While the previous principles exploited system structure, last five principles suggest techniques for speeding up a key system routine in isolation.

11. Optimize the expected case

While systems can exhibit a range of behaviors, the behaviors often fall into a smaller set called the “expected case”. For example, well-designed systems should mostly operate in a fault- and exception-free regime. A second example is a program that exhibits spatial locality by mostly accessing a small set of memory locations. Thus it pays to make common behaviors efficient, even at the cost of making uncommon behaviors more expensive.

Heuristics such as optimizing the expected case are often unsatisfying for theoreticians, who (naturally) prefer mechanisms whose benefit can be precisely quantified in an average or worst-case sense. In defense of this heuristic, note that every computer in existence optimizes the expected case at least a million times a second using caching, prefetching etc.

Note that determining the common case is best done by measurements and by schemes that automatically learn the common case. However, it is often based on the designer’s intuition. Note that the expected case may be incorrect in special situations or may change with time.

11a. Use caches

In general, caches allow designers to use modular structures and indirection, with gains in flexibility, and yet regain performance in the expected case.

You might be wondering: if caches are so great, why don’t we just make bigger caches and keep all of our data in them? Unfortunately, this is where we run into more fundamental laws like those of physics. If you want a fast cache, it has to be small, as issues like the speed-of-light and other physical constraints become relevant. Any large cache by definition is slow, and thus defeats the purpose. Thus, we are stuck with small, fast caches; the question that remains is how to best use them to improve performance.

12. Add state for speed

If an operation is expensive, consider maintaining additional but redundant state to speed up the operation like secondary indices in databases. Note that maintaining additional state implies the need to potentially modify this state whenever changes occur.

12a. Compute incrementally

To avoid recomputing the state added for speed, this principle can be used without adding state by exploiting existing state by incrementally computing the new state from the change/delta incrementally after every change or batch of change.

12b. Work in the background

When there is continuous stream of work to do, it is often a good idea to do small parts of it in the background to increase efficiency and to allow for grouping of operations. There are three benefits of doing work in the background — increased efficiency, the possibility of final work reduction and better use of idle time and hardware utilization.

13. Optimize degrees of freedom

It helps to be aware of the variables that are under one’s control and the evaluation criteria used to determine good performance. Then the game becomes one of optimizing these variables to maximize performance.

14. Use special techniques for finite universes such as integers

When dealing with small universes, such as moderately sized integers, techniques like bucket sorting, array lookup, and bitmaps are often more efficient than general-purpose sorting and searching algorithms.

15. Use algorithmic techniques to create efficient data structures

Efficient algorithms can greatly improve system performance. Algorithmic approaches include the use of standard data structures as well as generic algorithmic techniques , such as divide-and-conquer and randomization. The algorithm designer must, however, be prepared to see his clever algorithm become obsolete because of changes in system structure and technology. The real breakthroughs may arise from applying algorithmic thinking as opposed to merely reusing existing algorithms.

16. Learn from history

Optimize system by adding mechanisms to automatically learn from the past data to predict the future by using heuristics or even, machine learning. Such approaches are common in operating systems (and many other places in Computer Science, including hardware branch predictors and caching algorithms). Such approaches work when jobs have phases of behavior and are thus predictable; of course, one must be careful with such techniques, as they can easily be wrong and drive a system to make worse decisions than they would have with no knowledge at all.

17. Use Randomness

When the policy has to make optimal decision in an non-deterministic system, using a randomized approach is often a robust and simple way of doing so. Random approaches has at least three advantages over more traditional decisions. First, random often avoids strange corner-case behaviors that a more traditional algorithm may have trouble handling. Second, random also is lightweight, requiring little state to track alternatives. Finally, random can be quite fast. As long as generating a random number is quick, making the decision is also, and thus random can be used in a number of places where speed is required. Of course, the faster the need, the more random tends towards pseudo-random.

Epilogue

In the end, it all boils down to one principle for optimization,

Divide and Conquer, then Measure, Monitor and Optimize.

Divide the system into sub-systems, components, services and modules, divide the resources, divide the problem, divide the operations, divide the specification, divide time, divide space… pretty much everything, then start measuring performance, monitoring the system and components until you figure out the bottlenecks and then, can optimize to conquer the performance.

Performance problems cannot be solved only through the use of Zen meditation. Jeffrey C. Mogul

The best of principles must be balanced with wisdom to understand the important metrics, with profiling to determine bottlenecks, and with experimental measurements to confirm that the changes are really improvements without falling into the pit-fall of premature optimization or over optimization.

Premature optimization is the root of all evil. Donald Knuth

Navigation

This article is part of the series on System Manifesto : Wisdom, Philosophy and Principles.

In this series of System Manifesto, the other sections are:

Reference

- Varghese, George. Network algorithmics. Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2010.

- Raymond, Eric S. The art of Unix programming. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2003.

- Arpaci-Dusseau, Remzi H., and Andrea C. Arpaci-Dusseau. Operating systems: Three easy pieces. Vol. 151. Wisconsin: Arpaci-Dusseau Books, 2014.

- Lampson, Butler W. “Hints for computer system design.” ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review. Vol. 17. №5. ACM, 1983.

- Hunt, Andrew, David Thomas, and Ward Cunningham. The pragmatic programmer: from journeyman to master. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2000.

Originally published at https://www.linkedin.com on June 24, 2018.