Building event-driven architecture

Building event-driven architectureby Jayanth Kumar

So, you have decided to go the event-driven route of building your enterprise application using the event-sourcing paradigm after reading my old article — Architecting Event-driven Systems the right way but for deciding on the core of your application — the datastore, you start contemplating which will be the right datastore for your architecture based on your requirements. You revisit the possible database choices, relook at the business requirements, and then, comes the problem:

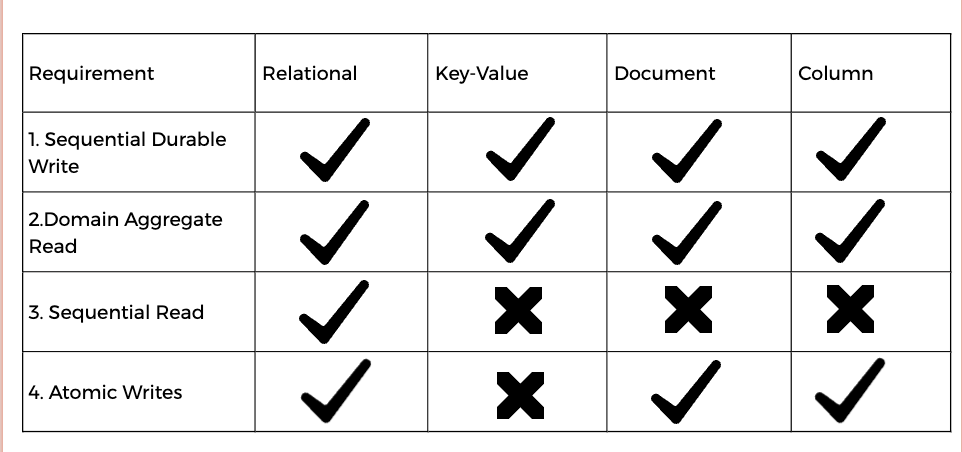

There are multiple requirements for Event Store and thus, different database strategies for using event sourcing for such requirements. How can you ahead and choose the right database based on the event-sourcing requirement?

Before we dive deep into the requirements, let’s go through the basic terms used in event sourcing.

State — A state is a description of the status of a system waiting to execute a transition.

Transition — A transition is a change from one state to another. A transition is a set of actions to execute when a condition is fulfilled or an event is received.

Domain Event — The entity that drives the state changes in the business process.

Aggregates — Cluster of domain objects that can be treated as a single unit, modeling a number of rules (or invariants) that always should hold in the system. Can also, be called “Event Provider” as “Aggregate” is really a domain concept and an Event Storage could work without a domain.

Aggregate Root — Aggregate Root is the mothership entity inside the aggregate controlling and encapsulating access to its members in such a way as to protect its invariants.

Invariant — An invariant describes something that must be true within the design at all times, except during a transition to a new state. Invariants help us to discover our Bounded Context.

Bounded Context — A Bounded Context is a system boundary designed to solve a particular domain problem. The bounded context groups together a model that may have 1 or many objects, which will have invariants within and between them.

Sequential Durable Write — Be able to store state changes as a sequence of events, chronologically ordered.

Domain Aggregate Read — Be able to read events of individual aggregates, in the order they persisted.

Sequential Read — Be able to read all events, in the order they were persisted.

Atomic Writes — Be able to write a set of events in one transaction, either all events are written to the event store or none of them are.

Let’s walk through different database types and dive deep into how they will support the above requirements.

Relational Database

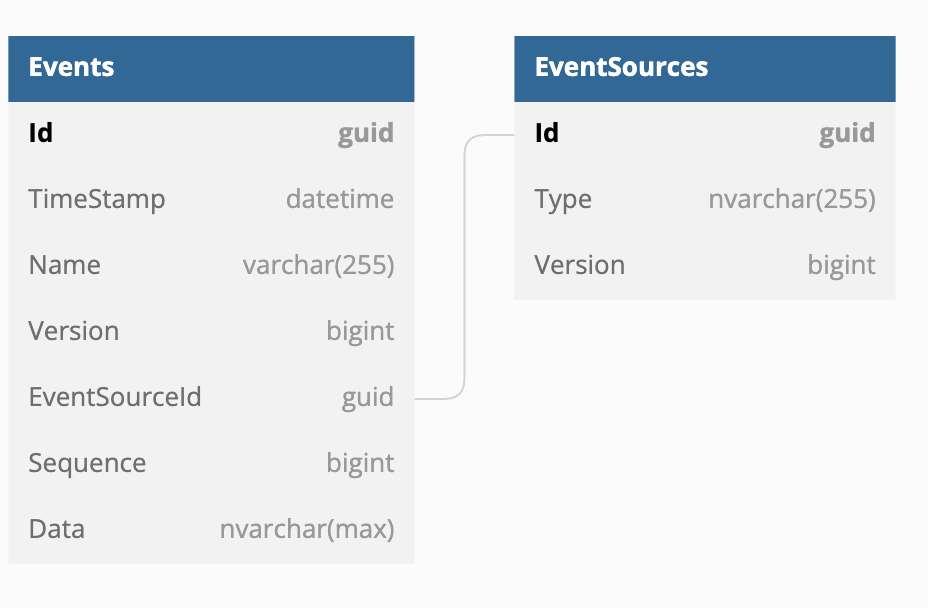

In a relational database, event sourcing can be implemented with only two tables, one to store the actual Event Log, storing one entry per event in this table and the other to store the Event Sources. The event itself is stored in the [Data] column. The event is stored using some form of serialization, for the rest of this discussion the mechanism will be assumed to be built-in serialization although the use of the memento pattern can be highly advantageous.

A version number is also stored with each event in the Events Table as an auto-incrementing integer. Each event that is saved has an incremented version number. The version number is unique and sequential only within the context of a given Event Source (aggregate). This is because Aggregate Root boundaries are consistency boundaries. On the other hand, Sequence, the other auto-incrementing integer is also, unique and sequential and stores the global sequence of events based on TimeStamp.

The [EventSourceId] column is a foreign key that should be indexed; it points to the next table which is the Event Sources table.

The Event Sources table is representing the event source provider (aggregates) currently in the system, every aggregate must have an entry in this table. Along with the identifier, there is a denormalization of the current version number. This is primarily an optimization as it could be derived from the Events table but it is much faster to query the denormalization than it would be to query the Events table directly. This value is also used in the optimistic concurrency check. Also included is a [Type] column in the table, which would be the fully qualified name of the type of event source provider being stored.

To look up all events for an event source provider, the query will be:

SELECT Id, TimeStamp, Name, Version, EventSourceId, Sequence, Data FROM Events

WHERE EventSourceId = :EventSourceId ORDER BY Version ASC;

To insert a new event for a given event source provider, the query will be:

BEGIN;

currentVersion := SELECT MAX(version) FROM Events

WHERE EventSourceId = :EventSourceId;

currentSequence := SELECT MAX(Sequence) FROM Events;

INSERT INTO Events(TimeStamp, Name, Version, EventSourceId, Sequence, Data)

VALUES (NOW(),:Name, :currentVersion+1, :EventSourceId, :currentSequence+1, :Data);

UPDATE EventSources SET Version = currentVersion+1 WHERE EventSourceId = :EventSourceId;

COMMIT;

Key-Value Store

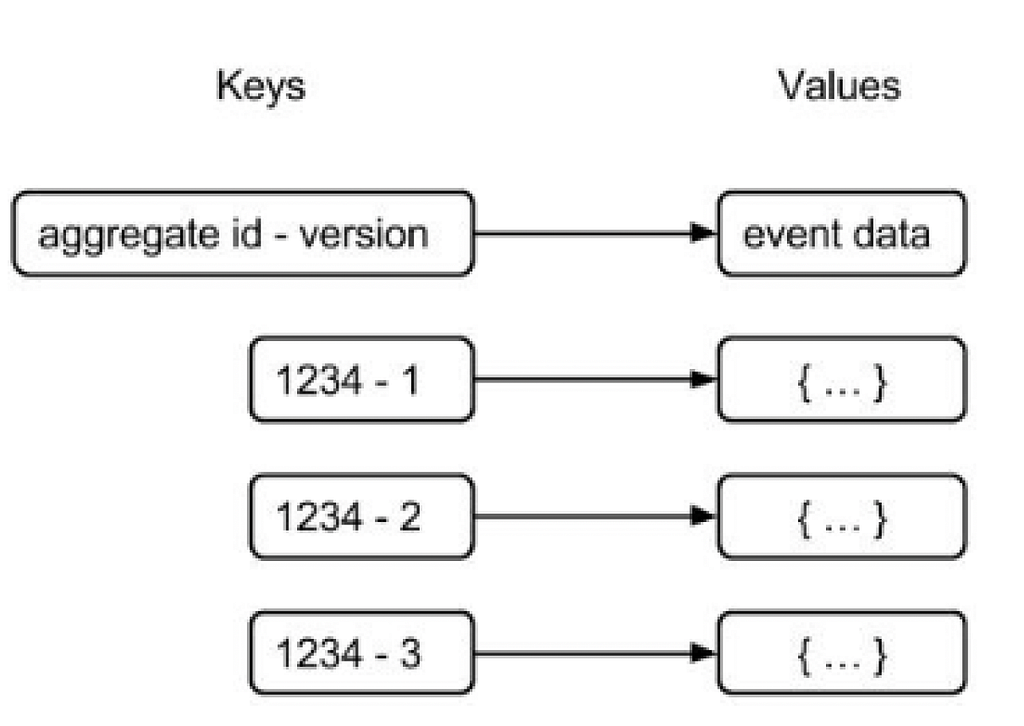

In a key-value store, an event can be modeled by constructing the key as a combination of the aggregate id and the version number. The serialized event data can be stored as the corresponding value. This method of constructing the key enables the chronological storage of events for a specific aggregate. To access data from the key-value store, knowledge of the key is required. It might be feasible to retrieve events for a particular aggregate by knowing only its aggregate id and incrementing the version number until a key is not found. However, a challenge arises when attempting to retrieve events for any aggregate, as no portion of the key is known. Consequently, it becomes impossible to retrieve these events in the order they were stored. Additionally, it’s important to note that many key-value stores lack transactional capabilities.

Document Database

Using a document database allows for the storage of all events associated with an aggregate within a single document, or alternatively, each event can be stored as an individual document. To maintain chronological order, a version field can be included in the document to store the events. When all events pertaining to an aggregate are stored in the same document, a query can be executed to retrieve them in the order of their version numbers. As a result, the returned events will maintain the same order as they were stored.

However, if multiple events from different aggregates are stored within a single document, it becomes challenging to retrieve them in the correct sequence. One possible approach is to retrieve all events and subsequently sort them based on a timestamp, but this method would be inefficient. Thankfully, most document databases support ACID transactions within a document, enabling the writing of a set of events within a single transaction.

Column Oriented Database

In a column-oriented database, events can be stored as columns, with each row containing all events associated with an aggregate. The aggregate id serves as the row key, while the events are stored within the columns. Each column represents a key-value pair, where the key denotes the version number and the value contains the event data. Adding a new event is as simple as adding a new column, as the number of columns can vary for each row.

To retrieve events for a specific aggregate, the row key (aggregate id) must be known. By ordering the columns based on their keys, the events can be collected in the correct order. Writing a set of events in a row for an aggregate involves storing each event in a new column. Many column-oriented databases support transactions within a row, enabling the writing process to be performed within a single transaction.

However, similar to document databases, column-oriented databases face a challenge when attempting to retrieve all events in the order they were stored. There is no straightforward method available for achieving this outcome.

Postgres

While Postgres is commonly known as a relational database management system, it offers features and capabilities that make it suitable for storing events in an Event Sourcing architecture.

Postgres provides a flexible data model that allows you to design a schema to store events efficiently. In Event Sourcing, you typically need an Events table that includes fields such as a global sequence number, aggregate identifier, version number per aggregate, and the payload data (event) itself. By designing the schema accordingly, you can easily write queries that efficiently perform full sequential reads or search for all events related to a specific event source (aggregate) ID.

Postgres also offers transactional support, ensuring ACID (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability) guarantees. This means that events can be written and read in a transactional manner, providing data integrity and consistency.

The append-only policy, a fundamental aspect of Event Sourcing, can be enforced in Postgres by avoiding UPDATE or DELETE statements on event records. This way, events are stored chronologically as new rows are inserted into the table.

Additionally, Postgres is a mature technology with wide adoption and a strong ecosystem of tools and libraries. It provides a range of performance optimization techniques, indexing options, and query optimization capabilities, enabling efficient retrieval and processing of events.

While Postgres may not offer some of the specialized features specific to event-sourcing databases, with careful design and optimization, it can serve as a reliable and scalable event store for Event Sourcing architectures.

Cassandra

Cassandra can be used as an event store for Event Sourcing, but there are some considerations to keep in mind.

Cassandra is a highly scalable and distributed NoSQL database that offers features such as peer-to-peer connections and flexible consistency options. It excels in handling large amounts of data and providing high availability.

However, when it comes to guaranteeing strict sequencing or ordering of events, Cassandra may not be the most efficient choice. Cassandra’s data model is based on a distributed and partitioned architecture, which makes it challenging to achieve strong sequencing guarantees across all nodes in the cluster. Ensuring strict ordering typically requires leveraging Cassandra’s lightweight transaction feature, which can impact performance and should be used judiciously as per the documentation’s recommendations.

In an Event Sourcing scenario where appending events is a common operation, relying on lightweight transactions for sequencing events in Cassandra may not be ideal due to the potential performance cost.

While Cassandra may not provide native support for strong event sequencing guarantees, it can still be used effectively as an event store by leveraging other mechanisms. For example, you can include a timestamp or version number within the event data to order events chronologically during retrieval.

Additionally, Cassandra’s scalability and fault-tolerance features make it suitable for handling large volumes of events and ensuring high availability for event-driven architectures.

MongoDB

MongoDB, a widely used NoSQL document database, offers high scalability through sharding and schema-less storage. It allows easy storage of events due to its schema-less nature.

MongoDB’s flexibility and schema-less nature allow for easy storage of event data. You can save events as documents in MongoDB, with each document representing an individual event. This makes it straightforward to store events and their associated data without the need for predefined schemas.

To ensure the ordering and sequencing of events, you can include a timestamp or version number within each event document. This enables you to retrieve events in the order they were stored, either by sorting on the timestamp or using the version number.

MongoDB also provides high scalability through sharding, allowing you to distribute your event data across multiple servers to handle large volumes of events.

However, there are certain considerations when using MongoDB as an event store. MongoDB traditionally supported only single-document transactions, which could limit the atomicity and consistency of operations involving multiple events. However, MongoDB has introduced support for multi-document transactions, which can help address this limitation.

Another challenge with MongoDB as an event store is the lack of a built-in global sequence number. To achieve a full sequential read of all events, you would need to implement custom logic to maintain the sequence order.

Additionally, MongoDB’s ad hoc query capabilities and scalability make it a strong choice for event storage. However, transactional support and event-pushing performance may require careful consideration and optimization.

Kafka

Kafka is often mentioned in the context of Event Sourcing due to its association with the keyword “events.” Using Kafka as an event store for Event Sourcing is a topic of debate and depends on specific requirements and trade-offs. Kafka’s design as a distributed streaming platform makes it a popular choice for building event-driven systems, but there are considerations to keep in mind.

Kafka’s core concept revolves around the log-based storage of events in topics, providing high throughput, fault tolerance, and scalable message processing. It maintains an immutable, ordered log of events, which aligns well with the append-only nature of event sourcing.

However, using Kafka as an event store for Event Sourcing introduces some challenges. One key consideration is the trade-off between storing events for individual aggregates in a single topic or creating separate topics for each aggregate. Storing all events in a single topic allows full sequential reads of all events but makes it more challenging to efficiently retrieve events for a specific aggregate. On the other hand, storing events in separate topics per aggregate can optimize retrieval for individual aggregates but may pose scaling challenges due to the design of topics in Kafka.

To address this, various strategies can be employed. For example, you can create a topic per aggregate and use partitioning to distribute the events across partitions. However, ensuring an even distribution of entities across partitions and handling the restoration of global event order can introduce additional complexities.

Another consideration is access control and security. When using Kafka as an event store, it’s important to manage access to the Kafka instance to ensure data privacy and integrity since anyone with access can read the stored topics.

Furthermore, it’s worth noting that using Kafka as an event store deviates from the traditional Event Sourcing principle of storing events before publishing them. With Kafka, storing and publishing events are not separate steps, which means that if a Kafka instance fails during the process, events may be lost without knowledge.

EventStore

“EventStore” is a purpose-built database that aligns well with the principles and requirements of Event Sourcing. It is a popular option written in .NET and is well-integrated within the .NET ecosystem.

Event Store, as the name suggests, focuses on efficiently storing and managing events. It offers features and capabilities that are well-suited for event-driven architectures and Event Sourcing implementations.

One key feature of Event Store is its ability to handle projections or event-handling logic within the database itself. This allows for efficient querying and processing of events, enabling developers to work with events in a flexible and scalable manner.

Event Store provides the necessary mechanisms to store events in an append-only fashion, ensuring that events are immutable and ordered. It allows you to store events for different aggregates or entities in a single stream, making it easy to retrieve events for a specific aggregate in the order they were stored.

Additionally, Event Store offers strong transactional support, allowing for ACID (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability) guarantees when working with events. This ensures that events are persisted reliably and consistently, maintaining data integrity.

Event Store also provides features for event versioning, enabling compatibility and evolution of event schemas over time. This is important for maintaining backward compatibility and handling changes to event structures as the application evolves.

Furthermore, Event Store typically offers built-in features for event publishing and event subscription mechanisms, facilitating event-driven communication and integration within an application or across microservices.

However, a key feature of “EventStore” is that projection (or event handling) logic is placed and executed within the Event Store itself using Javascript. While this is a tempting proposition, it diverges from our view that the Event Store should store events, and that projection logic should be handled by the consumers themselves. This allows us a greater degree of flexibility over how to handle our events and not being limited to the functionality of Javascript logic available in the “EventStore” database.

Redis Streams

Redis Streams differs from traditional Redis Pub/Sub and functions more like an append-only log file. It shares conceptual similarities with Apache Kafka.

Redis Streams allow you to append new events to a stream, ensuring that they are ordered and stored sequentially. Each event in the stream is associated with a unique ID, providing a way to retrieve events based on their order of arrival. Additionally, Redis Streams support multiple consumers, enabling different components or services to consume events from the same stream.

When using Redis Streams as an event store, you can store event data along with any necessary metadata. This allows you to capture the essential details of an event, such as the event type, timestamp, and data payload. By leveraging the features provided by Redis Streams, you can efficiently publish, consume, and process events in a scalable manner.

It’s important to note that while Redis Streams offer a convenient and performant solution for event storage, there are considerations to keep in mind. For example, ensuring data durability and persistence may require additional configuration and replication mechanisms. Additionally, access control and security measures should be implemented to safeguard the event data stored in Redis Streams.

In conclusion, each data store has its strengths and limitations for Event Sourcing. It is essential to consider factors such as scalability, consistency, sequencing, transactionality, and query support when selecting a suitable data store for an event-sourced system.

There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch.

Picking the Event Store for Event Sourcing was originally published in Technopreneurial Treatises on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

tags: